Two American Chestnut Trees Planted at Freedom Park on Arbor Day 2022

Native Castanea pumila, or Allegheny chinquapin, is a type of chestnut tree that supports pollinators and produces delicious nuts. It grows in the Country Roadside Garden of the Williamsburg Botanical Garden and Freedom Park Arboretum.

A second annual Earth Day and Arbor Day celebration on Saturday, April 23, at 10:30 AM will include the planting of two wild-type American chestnut seedling trees at Freedom Park in James City County, Virginia. The celebration results from a collaboration between the Clean County Commission, and volunteers at the Williamsburg Botanical Garden and Freedom Park Arboretum, with support from the Freedom Park staff.

One tree will be planted in the Pine-Hardwoods section of the Garden, and the other will be planted in the historic Free Black Settlement area, symbolically linking these two areas of the park together in the new Arboretum.

American chestnut trees, Castanea dentata, were once common across much of central and eastern North America, before a fungus, accidentally introduced from Asia, decimated the population beginning around 1905. Chestnut trees were commonly found in the Piedmont and mountainous areas of the state. Chestnut trees were documented by early British settlers in 1607-1608 in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, and the remains and shoots of old chestnut trees, previously damaged by the fungus, still grow in the Williamsburg area, including on the campus of the College of William and Mary.

Freedom Park has been archaeologically investigated over the years by Alain C. Outlaw, James City County resident. One group of discovered sites dates back to the nineteenth century and they were found in an area labeled “Free Negro Settlement full of Cabins and Paths” on an 1863 Confederate map of the county. This research, combined with information provided by historians, architectural historians, and material culture curators, led to the reconstruction, by 2007, of examples of structures that likely would have been present in the current park.

A Tree Steward project to replant food-bearing and other native trees around the reconstructed cabins in the Settlement area began around 2018. Replanting a chestnut tree in this area helps to further restore species once available for food and timber in James City County.

The Williamsburg Botanical Garden includes many woody species indigenous to James City County, including an Allegheny chinquapin, Castanea pumila, which is a closely related species of the American chestnut and produces edible nuts. While subject to the same fungus, it has so far remained healthy. Garden volunteers, including Peninsula Tree Stewards, hope to also reestablish the American chestnut within the arboretum. The two new trees will be close enough together for cross-pollination.

American chestnut trees, which are members of the same Fagaceae family as beech and oak trees, host 125 different species of butterflies and moths. They also provide nectar for pollinators, offer shelter for nesting, and will eventually produce nuts to sustain wildlife. Chestnuts are highly nutritious, rich in protein, and were important in the diet of indigenous cultures. European settlers prized chestnut trees. They became an important part of the economy and early American culture.

The two seedling trees that will be planted at Arbor Day were raised by the American Chestnut Foundation. The ACF sells wild-type seedling trees to members each March as a part of their efforts to reestablish a population of chestnut trees in Eastern North America. Local Master Gardener Tree Stewards purchased the trees in 2021 and have allowed the trees to grow in pots over the past year, in preparation for planting them out this spring.

Reintroducing a Beloved but Almost Extinct Tree

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was once a dominant tree of the eastern United States hardwood forest. It was magnificent growing straight, tall (up to 100 ft), and massive (trunk diameters could exceed 10 feet). It was also important commercially: the wood was resistant to rot, the tree produced nuts edible by both animals and humans, and it was a fast grower.

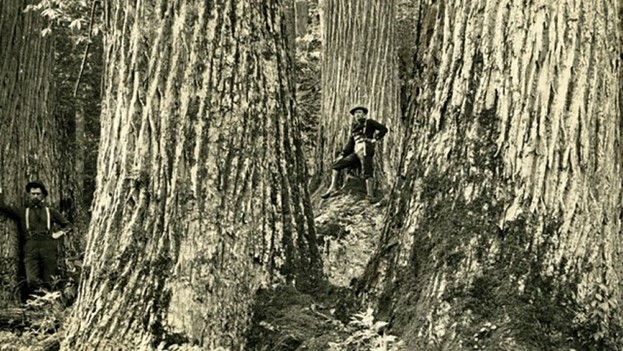

In Virginia, the tree grew primarily in the western portion of the state and generally could be found in and near the Appalachian Mountain range from northern Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama up into the Northeast. While the eastern United States is usually thought of as the historic home of the American chestnut, the tree also grew in Michigan. There were an estimated 3-4 billion American chestnut trees accounting for around 25% of the trees in the forest. The photo below was taken in the second half of the 19th century and illustrates the size of the trees.

Photo by the American Chestnut Foundation from a July 29, 2021, USDA Forest Service Article in Forestry, usda.gov

In the early 1900s disaster struck, coming in the form of a fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) arriving in Asian chestnut trees. Over thousands of years, the Asian trees had developed a resistance to the pathogen, but it quickly infected American chestnuts. The disease was termed Chestnut blight. Per the Forest Pathology website (https://forestpathology.org/canker/chestnut-blight/), the blight was a canker disease, causing infected branches and stems to die quickly. The cankers “grow rapidly and in most cases continue to develop until the stem is girdled and killed; then they continue to colonize the dead tree.”

A forester at the Bronx Zoo identified the disease in 1904. By the 1950s virtually all American chestnuts had been destroyed and the tree was considered “functionally extinct.” In a quirk of nature, the blight killed the above-ground portion, but the root system could survive. Sprouts grew out of these root systems but generally could grow no higher than 15 feet before being killed by the blight. The pathogen has persisted in the stumps of dead American chestnuts and is able to live in some types of oaks without destroying them.

Chestnut Tree Conservation

A relatively small number of American chestnuts have been found growing wild in recent years. A recent National Public Radio (NPR) article by American University Radio WAMU 88.5 cited several locations in D.C., Maryland and Virginia where the trees have been discovered. The largest number, almost 100, were found in the Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland. Most of these trees were small but one tree was 78 ft high. The number of American chestnuts that have been able to survive to reach mature heights is very small.

American Chestnut Leaves with Nuts and Burrs. Photo by Timothy van Vliet. From Wikipedia, used under terms of Creative Commons Attribute-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

As noted in their 2017-2027 Strategic Plan, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) was established with the mission “to return the American chestnut to its native range” in the eastern United States. Various approaches are being used to breed blight resistant varieties:

- Cross-breeding surviving American chestnuts that have shown themselves to be at least partially blight resistant.

- Cross-breeding American chestnuts with the more blight-resistant Asian chestnuts, then cross-breeding the resultant plant back with the American chestnut to try and capture more of the American chestnut traits while retaining the blight resistance of the Asian chestnut.

- Injecting the American chestnut tree with a virus that suppresses the ability of the blight to cause damage. The method has had mixed results in various parts of the world.

- Genetically modifying the American chestnut with genes that increase blight resistance. So far, the most effective gene has been one from wheat. The trees with modified genes would then be crossbred with surviving American chestnut trees. This would result in half the offspring inheriting the protective gene but still being 100% American chestnut.

TACF is also experimenting with various methods of reintroducing the American chestnut into its natural environment. One example is a cooperative effort among the US Forest Service, the University of Vermont, and TACF to plant improved blight-resistant American chestnuts in the Green Mountain National Forest.

The TACF website (https://acf.org) provides more detailed information about the American chestnut and their efforts to reintroduce the tree to its native range in the eastern United States. The new Williamsburg Botanical Garden and Freedom Park Arboretum join the American Chestnut Foundation’s efforts to save the American chestnut tree by planting these wild-type chestnut trees in the new arboretum.

Elizabeth McCoy and Patsy McGrady are both Master Gardener Tree Stewards and members of the James City County Williamsburg Master Gardener Association. Both have participated in the effort to create an arboretum at Freedom Park, along with MGTS Judy Kenshaw-Ellis and Dr. Donna M. E. Ware, who also contributed to this article. All photos by Elizabeth McCoy, unless otherwise noted.