Natural Plant Fertilizers for Your Garden

How do you fertilize your garden without buying any fertilizer? That is a key question for gardeners and farmers throughout the world today, as it was a key concern for our ancestors who couldn’t purchase commercial fertilizers for their fields. Soil must be fed to remain productive. Many popular crops, like corn and cotton, deplete the soil after just a few years. Our ancestors learned to use many natural fertilizers to keep their soil productive.

The Importance of Nitrogen to All Life

Plants require nitrogen to thrive and produce new growth. In fact, all life forms require nitrogen because it is an important part of our DNA. Plants that don’t get enough nitrogen look sickly and stunted. Plants, and other life forms will die without sufficient nitrogen. Starving plants draw nitrogen from older leaves to fuel new growth. We notice this when healthy leaves begin to turn yellow. Nitrogen, one of the most abundant elements on Earth, is found in all living things, including in animal waste products. Manure and urine are some of the oldest forms of ‘fertilizer’ used to feed the soil.

Members of the pea family of plants can ‘fix’ nitrogen on their roots. All members produce their seeds in pods, like a pea or a bean.

Nitrogen is a gas, and scientists believe that our atmosphere contained nitrogen even before it contained oxygen. It is the most abundant gas in our atmosphere today. Over half of each breath we take contains nitrogen. But most plants can’t use the simple nitrogen (N2) molecules found in air. They require the more complex molecules of nitrogen oxide, NO, and nitrogen dioxide, NO2. Rain can even contain nitrogen dioxide that enriches the soil, because lightening can cause nitrogen and oxygen to fuse into NO2 in the atmosphere during storms.

Manufactured fertilizers like ammonia (NH3) and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) require heat and pressure to join nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen together into fertilizers that can be added to soil. These fertilizers are expensive to make and to buy. Sometimes we use too much.

Waterways fill with algae and other weedy growth when too much nitrogen, and other fertilizers, run off from surrounding land. This harms animal life in the waterways.

Too Much Nitrogen Can Kill Plants and Harm Waterways

Too much of anything will cause problems. Too much nitrogen can reduce flower and fruit production, and can even kill a plant. Animal manure needs to compost before we use it around plants so we don’t burn them. Extra nitrogen that runs off from animal waste and from fertilizers applied to lawns and fields can kill waterways, especially if it encourages too much algae to grow in the water. These are a few of the many reasons to learn how to manage nitrogen in our garden soil so we don’t need to buy fertilizers. (This is also why we encourage everyone to clean up behind their pets.)

The ‘Three Sisters’ Enriched the Soil

Indigenous Native Americans knew how to work with plants to keep their garden soils productive. They grew three key food crops together, in a ‘hill,’ so that the plants could care for one another. They grew corn, beans and squash, ‘The Three Sisters,’ together to increase productivity and to manage their soil.

Squash, a member of the Cucurbitaceae family, can fix nitrogen on its roots if the soil is deficient, in cooperation with a different species of bacteria than members of the pea family employ.

Corn, a grain, was very important to eat yea-round both fresh and dried as corn meal. The corn stalks fed livestock and had many other uses. Gardeners planted corn at the center of each hill to support pole beans. Beans are an important source of plant protein and are enjoyed fresh or dried in a variety of ways. Native Americans considered both corn and beans sacred plants.

Bean plants were the key to this agricultural method because they can take nitrogen from the air and ‘fix’ it in nodules on their roots, in cooperation with Rhizobium and other bacteria that live in the soil. The nodules of nitrogen that form on the roots of all legumes, and in fact most every member of the Fabaceae (fəˈbāsēˌē) family fertilizes the soil with nitrogen for its own use, and for use by other plants. The bean vines fertilized the corn and the squash plants all season long as they grew together. Squash plants, with their gigantic leaves, helped mulch and retain moisture in each hill to make the most of summer rain and also fed the soil. Grown together, these three types of plants provided abundant food and improved the soil.

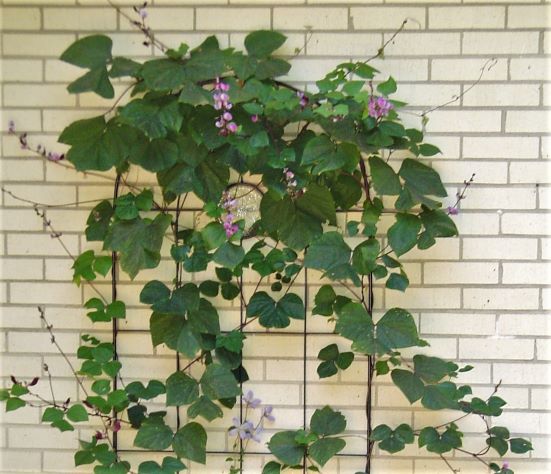

Purple Hyacinth Bean, Lablab purpureus, is native to Africa and grown throughout Asia. It was grown as a food crop in India as early as 2500 BC. It is poisonous if eaten raw.

The Fabaceae Family of Plants

There are many, many plants that can ‘fix’ nitrogen on their roots. All types of beans, peas and other pulses do this. But so do clovers and vetches, Wisteria, alfalfa and kudzu . There are more than 20,000 species of plants within the Fabaceae family, and over 700 different genera of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous annuals and perennial plants. Fabaceae is the third largest family of plants and species will be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Growing any species of the Fabaceae family will enrich the soil in your garden. Many gardeners ‘inoculate’ bean and pea seeds with bacteria before they plant them in areas where they haven’t grown before to insure that the necessary bacteria is available to work with the plants. These plants use the nitrogen needed for their own growth from the nodules on their roots and share the rest with other plants. Ornamental perennials in this family include Baptisia, Lupins and American Senna.

Actinorhizal Plants

Members of the Myricaceae (mirəˈkāsēˌē) family, about 50 species of shrubs and small trees, also fix nitrogen on their roots. Bacteria in the soil colonize nodules on their roots where they transform nitrogen, absorbed through the leaves, it into the molecules necessary for plant growth. Wax myrtle and swamp wax myrtle are both native trees naturalized in our area. Nearby plants also benefit from the nitrogen they add to the soil.

Many different plant families are known as “Actinorhizal plants” because they can form nitrogen storing nodules on their roots, in cooperation with the bacteria Frankia. These plants are important pioneer species to improve poor soils for prepare the way for other plant growth. The Myrica family of trees belongs to this group, along with the rose family, the beech family which includes oaks, the birch and the walnut families of trees. Interestingly, squash, a cucurbit, is also an Actinorhizal plant.

Evergreen American Wax Myrtle, Myrica cerifera fixes nitrogen on its roots using the bacteria Frankia. It supports wildlife in all seasons.

Plant materials, which contain some nitrogen, are key ingredients in compost. As the leaves, fruits and stems of plants decay, nitrogen, and other elements, are released back into the soil. This is a good reason to leave plants and fallen leaves to decay in the garden over winter or to gather and compost them as they fade.

Roots which have accumulated nodules of nitrogen enrich the deeper layers of soil and should be left in place to decompose. If a gardener wants to ‘tidy up’ and remove the bean and pea vines, or perennials belonging to the Fabaceae family when they stop producing, the plants should be cut at ground level and the roots left in place because the nodules on their roots contain so much nitrogen, which can be used by other plants. The same would be true of the Actinorhizal plants which also fix nitrogen on their roots.

A Complex Ecosystem in Living Soil

We have learned in recent years that plant roots work together with bacteria and fungi to ‘share’ nitrogen, sugars, and chemical information across long distances through the soil. In many parts of the world, nitrogen fixing trees are planted in and around gardens to help fertilize crops and improve the soil year to year. Some of these trees produce edible seed pods that can be eaten by people and fed to livestock. The trees enrich and protect the soil while also producing an edible crop.

Our soils form a complex ecosystem beneath our feet. Invisible and silent, we may not really understand how bacteria, fungi, insects and invertebrates interact with the intertwining roots of all of the plants in our garden to maintain a good balance of water and nutrients while they recycle all of the elements of life. Insects and invertebrates, like earthworms, process dead vegetation into rich humus which improves the fertility and water retention of our soil.

Native Wisteria frutescens belongs to the pea family of plants. Its seeds are poisonous to humans if ingested.

The Magic of Deep Roots

In addition to those plants which can fix nitrogen on their roots, other plants grow especially deep roots which absorb minerals from the deeper layers of soil, and make them available at the surface. These deep roots also break up compacted soil and even rock to transform it into usable, friable soil to support plantings.

Perennial comfrey’s roots may extend more than 6’ deep into the soil. It is valued for its leaves which can be used medicinally and fed to livestock, but also for the excellent, mineral rich fertilizer produced by its leaves. Leaves may be shredded and soaked in water to make ‘fertilizer tea,’ or they can be used as mulch. The minerals are released into the soil as comfrey leaves decompose. Kale, dandelions, borage, alfalfa, and fennel also have these very deep, mineral seeking roots.

Comfrey’s deep roots absorb minerals. It is a useful medicinal herb for topical use only. It is poisonous to ingest. Grow it for pollinators and brew its leaves into fertilizer tea. Symphytum officinale

Trees Improve Soil in Several Ways

Trees have much deeper and networked roots than herbaceous perennials, vegetables, or herbs. Planting trees with deep roots, which also fix nitrogen on their roots, delivers the largest amount of usable nitrogen and other minerals to your garden soil. Long-lived trees continue to improve the soil as they grow, year after year. Many trees in the Fabaceae family also produce edible seed pods which can be cooked or used as fodder for livestock. Leaves from these trees, used as mulch or in compost, help enrich the soil even more.

Since members of the Fabaceae family grow worldwide, some of these plants aren’t native in Eastern North America. Some nitrogen fixing trees that are common in our area, like the autumn olive and the summer blooming mimosa tree, are listed now as invasive plants because they seed themselves around so freely. Like kudzu vines, these trees were imported decades ago and were recommended to serve useful purposes . But they spread their seeds widely and crowd out native species. Other trees may be undesirable because of their thorns or the fruit they drop. Always choose plants with care, with full awareness of their uses and growth habits.

Common Nitrogen Fixing Trees in Our Area

All Oak trees, American Beech, and Birch trees can fix nitrogen on their roots, especially in poor soils.

Black Locust Robinia pseudoacacia – Beautiful spring flowers, a Lepidoptera host plant, supports wildlife, to 50’ in sun or part shade. All parts poisonous if ingested. Has both spines and thorns. Native plant in Zones 3a-8b.

Mimosa Albizia julibrissin – Beautiful pink summer flowers very attractive to pollinators introduced to the US from Asia in 1745 and now considered invasive. Highly ornamental in sun or partial shade, to 60’, grows on very poor soil and provides fodder for livestock. Zones 6a-9b.

Hazel Alder Alnus serrulata – Small East Coast native tree with high wildlife value, a Lepidoptera host plant, to 15’ in sun to part shade on clay and in wet soil. Insignificant flowers in late winter. Zones 4a-9b.

Wax Myrtle, Swamp Bayberry Myrica cerifera , M. caroliniesis Evergreen East Coast native shrubs or small trees with very high wildlife value, Lepidoptera host plants, to 25,’ 8’. Insignificant flowers support pollinators, and drupes from late summer through late fall support many species of birds. Both species grow in dappled shade or full sun or poor, moist or wet soil. 7a-10b, 7a-9b.

Kentucky Coffee Tree, Gymnocladus dioicus – A very large North American native tree to 60′ which stands bare much of the year. Its leaves open late and drop early. Leaves, seeds and pulp are poisonous if ingested by livestock, pets or people. A Lepidoptera host plant, its showy flowers attract pollinators in early summer. Native Americans roasted, ground, and made the seeds into a coffee like beverage, without any caffeine. Full sun in Zones 3a-8b.

Autumn Olive, Russian Olive Elaeagnus umbellata, E. angustifolia –These trees are considered highly invasive in our area. Introduced from Asia in the 1800s, they grows on poor soils and have high wildlife values and edible fruit. They are extremely persistent, with deep roots, and are difficult to eradicate once established. To 16’ in full sun. Zones 4a-9b, 2a-7b.

All Photos by E. L. McCoy

For More Information:

Aczel, Miriam. “What Is the Nitrogen Cycle and Why Is It Key to Life?” Frontiers for Young Minds. March 2019.

Alfrey, Paul. “Nitrogen Fixation”. The Permaculture Research Institute. February 2023.

Bloom, Jessie, Dave Boehnlein, Paul Kearsley (Illustrator). Practical Permaculture: for Home Landscapes, Your Community, and the Whole Earth. Timber Press. 2016.

Chalker-Scott, Linda. How Plants Work: The Science Behind the Amazing Things Plants Do. Timber Press. 2015.

Reza, Shamim. “Introducing Nitrogen Fixing Trees: Nature’s Solution to Curing N2 Deficiency.“ Permaculture Research Institute. October 2015.

Thornbro, Harold. “Chop and Drop for a Better Garden: Why and How?” Redemption Permaculture. February 2023.

Thornbro, Harold. “Eight Plants Commonly Used to Increase Soil Fertility.” Redemption Permaculture. February 2023.

“Trees Improve the Soil.” Common Pastures. February 2016.