A Winter Wildlife Garden- “Inviting the Stranger”

A Northern Cardinal hunts in the branches of a dogwood tree, a favorite source for both insects and drupes.

Cardinals nest in a large evergreen shrub beside my kitchen window. Though the shrub, Ligustrum, is frowned upon by many contemporary gardeners as invasive, the birds don’t know that. They delight in its abundant berries and the insects that visit year-round.

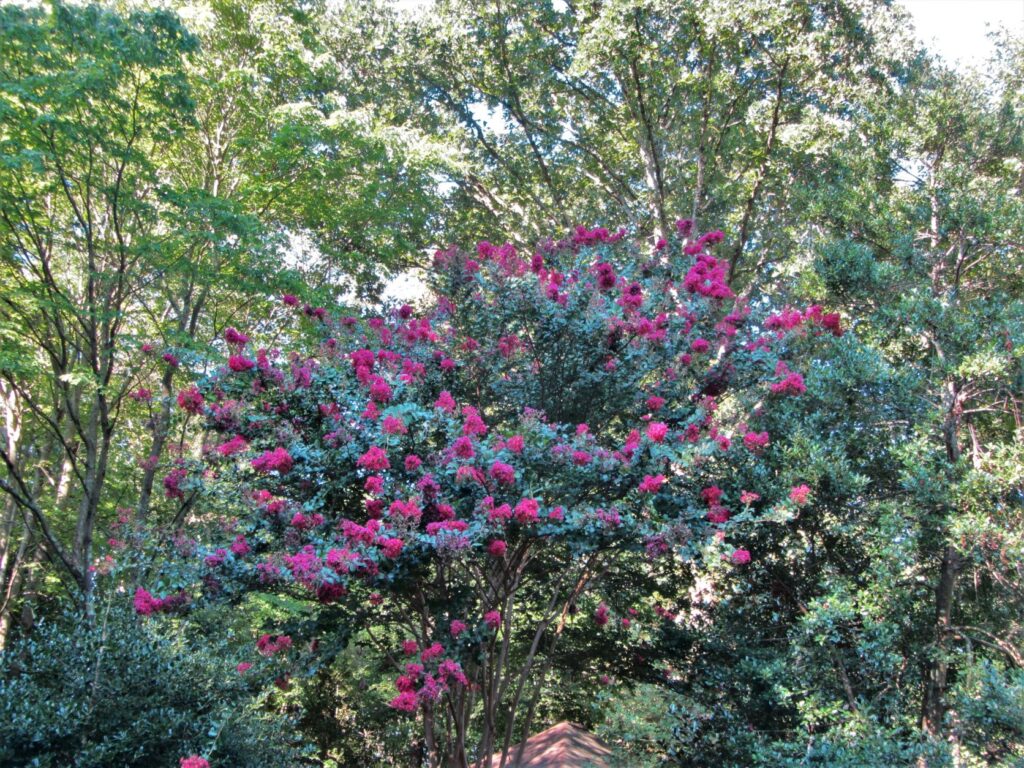

We delight in watching the birds come and go, even as they peer in the windows at us. We amuse one another. Cardinals, titmice and other birds also perch in the crape myrtle tree a little further out in the yard, and feed in the rose of Sharon shrubs growing at the top of the path.

As generations of song birds raise their young in the same shrubs beside our home, we no longer think of them as visitors to the garden. Along with families of squirrels, rabbits, turtles and skinks, our yard is their home also.

As Michael Carter Jr., of Carter Farms in Orange County, Virginia, explained on a recent episode of ‘Virginia Home Grown,’ it is traditional in West Africa to ‘invite the stranger’ when growing food and making gardens. He went on to observe that this includes inviting wildlife. As we offer shelter, food, and water for wildlife, we don’t know in advance what types of animals might show up. But we can expect surprises!

We have families of birds living in our yard, and in neighboring yards, throughout the entire year. Others come and go during their migrations. Next door, the neighbors tell us about watching red tailed hawks raising their young in a tall tree near their deck. We hear owls in the ravine at night and awaken to birdsong most mornings. Birds take wing from their hidden perches as we walk through our yard.

Meeting the Need

Attracting a variety of birds, and other wildlife to live and raise their young in our gardens, simply requires providing for their needs. Animals chiefly need varied and reliable food sources, shelter from the weather, safe perches where they can rest, and a source of fresh water. They also like their privacy and a sense of security, and can sense a welcoming spirit in the garden.

We stopped ‘feeding the birds’ with commercial feeders and seed long ago. A feeder rig or birdbath placed out in a lawn, without shrubbery and trees nearby, makes birds vulnerable to all sorts of predators and competitors while they eat, drink and bathe. Commercial seed mixes also attract rodents and bears, and the rodents can attract snakes and other predators. Bears, snakes, foxes and coyotes are spotted in our neighborhood, and in other parts of the Williamsburg area, from time to time.

To provide consistent water throughout the year, we place a shallow bowl of water, with some large rocks for perching, in a protected corner of the patio beside a potted shrub. It is important to clean and refresh water for wildlife regularly.

Instead of putting out feeders, we noticed where our birds build their nests, where they return again and again to feed, and where in the yard they like to perch. We quickly realized that our shrubs play a key part in providing food, shelter, nesting sites and security that allow the birds to raise generation after generation of young in our yard. And most surprisingly, the birds prefer the large, established shrubs growing nearest the house.

Multi-Tasking Trees and Shrubs

Many of these evergreen shrubs produce berries and have dense branch structures. Evergreens provide year-round shelter, and the house serves as a windbreak and source of warmth. But there is also security because snakes and other predators are less inclined to attack birds’ nests when they are near our home. Birds that rob others’ nests, like blue jays, are less likely to raid a nest that isn’t out in the open. Prickly shrubs like hollies and Pyracantha provide even more protection for nests.

Birds nest in an old Pyracantha shrub, which has sharp prickles. Orange berries disappear quickly because birds favor them in nearly winter.

But berry producing shrubs offer even more benefits, because they bloom in the spring and attract pollinating insects. Biologists tell us that birds need insects in their diets much more than they need seeds and the other treats we like to offer at feeders. Very few bird species can feed seeds to their young. Birds require a steady diet of insects to thrive and raise their chicks. And caterpillars, the larvae of butterflies and moths, are an especially important part of their diet.

Native trees, like oaks, redbud, and pines each attract hundreds of species of insects. They also shelter insect larvae in the cracks in their bark, through the winter and early spring. Just a few large, native trees can provide a steady supply of insects and insect larvae to hungry birds throughout the year. Even more insects and larvae may be found in the sheltered ground beneath large trees and shrubs, often living in the leaf litter or mulch under woody plants.

We have very few areas of lawn left at our home. But we have mature trees, mixed hedgerows of shrubs that produce a variety of food throughout the year, fruiting vines, expanses of ferns and flowering perennials, and large areas under moss or mulch. Birds can swoop from tree to shrub to ground and back in short hops, with cover always close at hand. Birds of prey perch in the treetops watching for voles (and other food), and woodpeckers attack a few snags that we have left for them.

A very old American beech tree provides seeds each fall, perches for birds of prey, snags for wood peckers, and it shelters squirrels.

During spring and summer, the living is easy for birds as well as for people. A friend introduced me to a family of sparrows who nested in a potted Boston fern on her deck, right outside of her dining room window. The fledglings flapped around on the deck for a while, summer after summer, until each brood was strong enough to fly.

But things get much tougher for wildlife after temperatures drop and the leaves have fallen, food becomes scarcer, and water sources freeze. A little planning and careful planting can transform a suburban yard into a year-round wildlife refuge.

Rose of Sharon seeds and crape myrtle seeds remain available all winter, even when their seed capsules are covered in snow and ice. Birds find shelter in a dense stand of bamboo.

Begin with What You Have

We begin a wildlife garden with whatever trees or shrubs already grow in our yard, and then plant additional useful varieties, particularly those native species well-adapted to our climate. Watch for seedlings to appear, and decide what can be left to grow, what needs to be moved, and what should be eliminated while the plants are small. Plant mixed borders, or hedgerows, where species of different heights, textures, colors, and forms blend together.

Bringing together the telluric energy of the earth with the energy of the sun to support the growth of a seed into a thriving plant, and then allowing that plant to feed a variety of wildlife species, anchors the creative energies of the universe into our gardens. We become co-creators of a life-sustaining and life enhancing garden. We personally benefit in countless ways.

Just as most people are happiest among friends and family, most trees and shrubs enjoy growing in community with others. This is how they grow in natural areas. Trees planted in groves prove safer near our homes since their roots grow together, intertwined, making it more difficult for a group of trees to blow over in a windstorm. Trees of various species and different heights attracts more species of insects and more species of birds, offering a variety of choices for food and shelter throughout the year.

Birds love Euonymous drupes and find shelter in its dense branches. This shrub, known as burning bush, draws lots of visitors until its drupes are gone. A better, native choice is E. americanus.

“Do No Harm”

A foundational principle of inviting wildlife to our gardens prohibits the use of insecticides. Chemicals like insecticides, herbicides and fungicides linger on plants, in the soil and water, and enter the food chains of many creatures- including humans. A wildlife gardener understands that insects become food for other creatures. We seek balance instead of using chemicals to eliminate living species.

Even snags left from fallen trees provide shelter and provide abundant insect food for birds as they slowly decompose, and return to the Earth. Jamestown Island

Recommendations for a Winter Wildlife Garden

Here is a baker’s dozen of easy to grow trees and shrubs, native or naturalized in Eastern Virginia (Zone 7B), which attract multiple species of birds. They are specifically chosen for this list because they all provide winter food in one form or another. They also provide shelter, safe perches and nesting spots, and are favored by the birds in living in our yard.

Camellia C. japonica, C. sinensis, C. sasanqua and various hybrids- Dense, evergreen shrubs to 12’ provide exceptional shelter and nesting sites for birds year round. Camellias bloom during the cooler months, supporting a wide variety of insects from October through April, depending on the cultivar. Woody capsules open, exposing seeds, in late summer and early fall. Highly ornamental, Asian Camellias were first imported to North America in 1797. They prefer acidic soil and partial to full shade, under trees and near buildings.

Birds find shelter and nesting sites within the dense network of Camellia branches. Broad evergreen leaves provide a windbreak and keep ice and snow away from nests. Birds can eat the many insects attracted to Camellias when in bloom.

Crepe Myrtle Lagerstroemia indica Deciduous ornamental tree or shrub to 30’, but most varieties smaller, cultivated for its bright flowers in shades of red, pink, lavender, and white which last approximately 100 days from July through September. Crepe Myrtle was brought to North America from Asia in 1790. It has naturalized and has been widely grown ever since.

Crepe Myrtle flowers attract butterflies and hummingbirds, as well as insects which hummingbirds and other birds eat. Many different birds eat the seeds which remain available all winter. Birds use Crepe Myrtles for shelter and nesting.

Dogwood Cornus florida- Deciduous ornamental spring blooming tree with colorful fall foliage and drupes to 40’. Virginia native

Dogwood attracts many different types of birds who nest, eat its fruits, or eat insects from the bark. Ninety-eight different species of birds eat Dogwood drupes including flickers, tanagers, woodpeckers, catbird, thrashers, bluebirds, and cardinals.

American Hazelnut, Filbert Coryalus americana and Coryalus cornuta- Deciduous, suckering shrubs grow into a dense thicket of small trees, offering excellent shelter and nesting sites for a variety of birds. Showy male catkins in late winter are decorative. Small nuts are edible, tasty, and attract a variety of wildlife. Virginia native grows to 12’.

Hazel trees bloom in late winter. These male catkins grow to several inches long, and disappear as the leaves unfold later in spring.

American Hazelnut attracts a wide variety of wildlife including songbirds, butterflies, squirrels, deer, turkeys, grouse, quail and a wide variety of insects. It is a valuable host plant for over 130 species of moths and butterflies. Nuts may be roasted and eaten or ground into flour. Wood may be coppiced, and the slender stems used for a variety of uses, including making baskets, barriers and plant supports.

Holly Ilex opaca and other species- Most holly species are evergreen, grow to 50’, and are covered in drupes in winter. Native Ilex verticillata, known as winterberry, is deciduous.

Holly species provide shelter and protected nesting sites for many birds. Late winter flowers provide an important nectar source for early pollinators. Over 49 avian species enjoy its fruits, including cardinal, mockingbird, catbird, brown thrasher, bluebirds, cedar waxwing, and robin.

Oak Quercus species- Deciduous or evergreen landscape trees to 100’ or more, depending on species. Oak, a keystone species in our region, is regarded by many biologists as the most important tree for sustaining a wide variety of wildlife and various genera support over 530 different species of Lepidoptera, in addition to a wide range of other insects.

Oak is one of the most important wildlife and landscape trees. Acorns support a variety of wildlife and are edible for humans. It attracts birds who nest, find shelter, eat its acorns, and eat insects in its bark and foliage Including woodpeckers, chickadees, titmice, cardinals, flickers, grouse, blue jays, meadowlarks, nuthatches, doves, thrushes, ducks, bobwhites, quail, grosbeaks, and scarlet tanagers.

Leatherleaf Mahonia blooms from December through early spring. This shrub has recently been added to the invasive species list in Virginia because the birds sow its seeds so efficiently, and it out competes many native plants.

Leatherleaf Mahonia, (Oregon Grape Holly) Berberis bealei- Ornamental evergreen shrub to 7’. Its thick, spiny leaves won’t be grazed by deer and provide important cover for birds. Clusters of yellow flowers in December through February mature into edible drupes. Beautiful as a foundation planting. This is an Asian species that looks very much like the North American native, Berberis aquifolium.

Grape holly offers winter flowers for nectar loving insects, and dark purple clusters of edible drupes by late spring feed a variety of birds and small mammals. Its dense cover, when established, offers shelter from the weather and protected nesting areas. Mahonia has naturalized in central and eastern Virginia and is pest-free. It recently was added to Virginia’s invasive species list.

Pine Pinus species- Evergreen tree to 100’ or more which produces seeds in cones. Pine species also support over 200 species of Lepidoptera, and other insects, attractive to birds. Virginia native species include loblolly, Eastern white pine, cedar pine, longleaf and Virginia pine.

Pine attracts birds to nest, roost, eat its seeds, and even eat its needles. Pine needles making excellent nesting material. Birds also eat the many insects attracted to pine trees. Pine is one of the most important trees for wildlife. Species attracted Include: woodpeckers, chickadees, grosbeaks, nuthatches, jays, dark eyed juncos, pine siskins, meadowlarks, woodpeckers, thrashers, warblers, grouse, robins, doves, cardinals, and finches.

Red Bud Cercis canadensis– Deciduous tree to 30′ which blooms in early spring, supporting many pollinating insects including specialist bees. Redbud hosts 12 lepidoptera species. Edible flowers and seedpods, which look like pea pods, ripen in autumn. Virginia native.

Redbud trees provide birds with a nearly continuous supply of insects and insect larvae throughout the year. Large, heart shaped leaves provide good cover from mid-spring through autumn. Quail, pheasants, goldfinches, and other birds feed on the seeds in winter, along with deer and small mammals.. Trees grow very gnarled with age, providing additional habitat for small animals.

This self-seeded red cedar is about eight years old and doesn’t yet produce drupes. Trees grow increasingly dense as they age.

Red Cedar Juniperus virginiana- Evergreen tree to 40’ with aromatic leaves and blue berries. Dense branches and fragrant, scale- like leaves provide exceptional protection for wildlife. Foliage is good for holiday decorations and its aromatic wood for storing clothing. Virginia native

Cedar provides shelter during bad weather, protected nesting and roosting sites for many birds, and over 54 species eat its fruit. Including cedar waxwing, purple finch, robin, evening grosbeak, warblers, flickers, mockingbird, bluebird, bobwhite, swallows, eastern kingbirds, jays, and cardinals.

Rose of Sharon supports pollinating insects and hummingbirds from May through September each year, and each flower produces abundant seeds.

Rose of Sharon Hibiscus syriacus– Deciduous shrub to 12’ with bright, showy flowers, which blooms continually from May through October. Woody seed capsule provide abundant seeds from autumn through spring. Tolerates partial shade, air pollution, heat, and wet soil. Asian shrub which self-seeds.

Rose of Sharon, H. syriacus, is one of the best flowering shrubs to attract wildlife year-round. It attracts pollinators all summer and produces abundant seeds for birds through the winter.

Rose of Sharon attracts pollinators, including hummingbirds and some specialized bees all summer, and feeds a wide variety of birds from its abundant seeds during much of the year.

Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipifera- Deciduous landscape tree to well over 100’ tall. Its spring blossoms are an important source of nectar for many pollinators, including hummingbirds and cedar waxwings. This is an especially beautiful tree with interest year-round. Virginia native

Tulip Poplar provides shelter, protected nesting and roosting sites for many birds, and many avian species eat both its flowers and seeds, and the insects living on it. Seed capsules linger throughout the winter, feeding squirrels, birds and deer. Liriodendron is a host plant for the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail and Spicebush Swallowtail, and the Viceroy butterflies. Leaves, buds, twigs and flowers support many types of wildlife, including small mammals and deer, during the summer.

Wax myrtle berries disappear quickly as the weather cools. They are an important food source for birds and other wildlife in late fall and early winter. This is M. cerifera, a native that often volunteers in our area.

Wax Myrtle, Bayberry Myrica cerifera, M. caroliniensis, and M. pensylvanica- Dense evergreen shrub to 40’ with small blue berries covered in fragrant wax, which may be rendered for a variety of uses. Small spring flowers attract nectar loving insects. Leaves host the Red-banded Hairstreak butterfly. Grows in dense colonies in a variety of conditions, including poor soils. Virginia native

Wax Myrtle berries are eaten by 86 species of birds, including robins, tufted titmouse, finches, chickadee, bluebirds, bobwhite, swallow, woodpeckers, cardinals, and finches. Its dense structure makes it an excellent shelter and nesting site.

Oldies Aren’t Always so Good…

Older homes often have shrubs that were marketed as ‘wildlife friendly’ decades ago, and now are considered either invasive, or at least a ‘nuisance plant’ because they seed themselves around. They are easy to grow and persistent, which allows them to out-compete many native plants. These include Asian Ligustrum ssp., known as privet; Elaeagnus umbellata, autumn olive; Euonymous alatus, burning bush; and Nandina japonica and other species and hybrids, known as heavenly bamboo. Some of these have become invasive because birds love them so much and spread them around. Nandina, prized in holiday decorations for decades, is highly poisonous, particularly for pets and for some birds. Birds usually avoid it when other foods are available.

Another highly poisonous shrub with high wildlife value is mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia. Evergreen mountain laurel, a Virginia native often found growing on the banks of rivers and ponds, grows in dense thickets, which provide wonderful cover. It supports hummingbirds and pollinating insects in early summer. Every part of the plant is highly poisonous to pets, domestic livestock, and humans, and so it didn’t make this list of recommended plants.

Gardeners will find a huge variety of named cultivars of most of the trees and shrubs highlighted here as good choices for a wildlife garden. Named cultivars have been selected for their size, their health, and for special characteristics, like leaf color or abundant fruiting. Even within a genus, various species offer a gardener choices to select the best plant for her available space and growing conditions.

When we ‘invite the stranger’ and welcome a variety of wildlife to our garden, we also invite joy. We open the door to deeper understandings of our world, and guarantee that we’ll make interesting discoveries every time we pause to listen and look at the life unfolding all around us.

Bibliography and Resources:

Adams, George. Birdscaping Your Garden: A Practical Guide to Backyard Birds and the Plants That Attract Them. Rodale Books. 1994.

Roth, Sally. Bird-by-Bird Gardening: The Ultimate Guide to Bringing In Your Favorite Birds- Year after Year. Rodale Books. 2006.

Tallamy, Douglas. Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (updated and expanded). Timber Press. 2007.

Tallamy, Douglas. The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees. Timber Press. 2021.

Bringing Birds to the Garden August 2021

Invitation to a ‘Homegrown National Park’ February 2022

All Photos by E. L. McCoy