The Compton Oak

by Rick Brown · Published · Updated

The former Colonial Williamsburg Garden Historian, Wesley Greene, had a discussion with Scott Hemler, Colonial Williamsburg’s nurseryman this year in August, about the origin of our famous Compton Oak. In this exchange, Greene raised questions about the “legend” of this tree and how it came to be planted on Nicholson Street in historic Williamsburg.

So, at Green’s suggestion, I began an investigation to see if the Archives at the Rockefeller Library could provide any additional information about the time period and date of transplanting this oak tree.

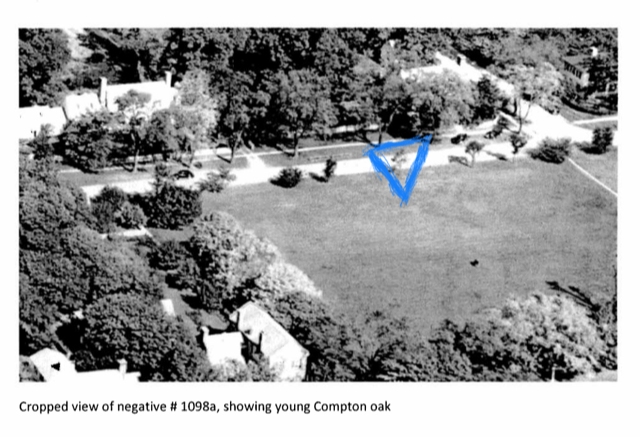

An aerial photo taken in 1940 of The Compton Oak as a small sapling. Photo Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s archives

A previous review of photographic records, Greene said, revealed that a number of years ago Don Parker, former Landscape Architect for the Foundation, gave the Rockefeller Library copies of the correspondence of Colonial Williamsburg’s first Landscape Superintendent, Justin B. Brouwers. In an e-mail, Greene stated that, “I have not seen them, and I do not know how extensive the correspondence is, but a trip to Archives would certainly be worthwhile.”

Portions of Brouwers’s correspondence are, in fact, now a part of the archival materials in the collection and provide an invaluable first-hand account of how and when the Compton Oak came to be located in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. A review was made on August 15, 2023. According to that correspondence, the Compton Oak was discovered by Brouwers in the wild in an area then known as “Boush (pronounced Bush) Creek, south of Norfolk, Virginia in 1937.”

Here is correspondence from Justin Brouwers to the U.S Department of Agriculture, Division of Plant Industry, dated February 3, 1947, seeking assistance to help identify the specific taxon:

“This tree was growing about twenty-five feet from the water’s edge near brackish water. It was dug and transplanted to Williamsburg in 1938. At the time of moving it [was] about 15’-18’ tall and had a trunk diameter from three to four inches at the ground. This tree grew no nearer than approximately one-half mile from Live Oak trees. Since transplanting the tree in Williamsburg, it has grown to a height of between thirty-five and forty feet, and its trunk diameter is now from 10 to 12 inches at the ground.

Will you please identify this specimen, giving us the Botanical name, if possible, and any other information you may have for us.”

Brouwers originally thought the tree was possibly a live oak, Quercus virginiana, or perhaps some sort of unidentified hybrid. But, after a few years he apparently became curious when it did not behave like other live oaks in the area. He enlisted the assistance of Dr. J.T. Baldwin, a prominent botanist and head of the Biology Department at William & Mary, to obtain a more positive identification. The tree was referred to simply as “Brouwers’s Oak” during this period.

A street view of the Compton Oak in 1979. Photo courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s archives.

Baldwin wrote to Ernest J. Palmer, the collector-botanist at Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum on January 27, 1947, and sent leaf, twig, and acorn samples to assist with the identification. Palmer was a noted botanical taxonomist specializing in the Quercus genera of oak trees.

Palmer responded promptly on January 31, 1947, saying that Baldwin’s “surmise as to it being a hybrid between the live oak and a deciduous species is certainly correct, and I think there can be no doubt that the other parent is the overcup oak (Quercus lyrata Walt.).”

It was fortunate that Baldwin involved Palmer since the Compton Oak was, in fact, discovered and first named in 1918 by his mentor Charles Sprague Sargent, who was the first Director of the Arnold Arboretum. Sargent made the discovery after a trip he made to the property of Miss C.C. Compton near Natchez, Mississippi. In his response, Palmer describes the origin of the Compton oak at length and verifies that the oak planted by Mr. Brouwers was, in fact, the same hybrid, Quercus x comptonae (sic.).

In the meantime, S.F. Blake, Senior Botanist at the United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Industry responded to Brouwers that:

“[n]ot being able to match your oak specimen here I sent it to Dr. Rehder at the Arnold Arboretum. He identifies it as a Quercus comptonae (sic.) Sarg.

Thus, Baldwin and Brouwers were initially corresponding independently with different experts at different locations and received the same conclusion from two different authorities, who were both employed at the Arnold Arboretum.

The Compton Oak was photographed again in April, 2023, from the same angle as the 1979 Street View photo, to show how much it had grown. Photo by Rick Brown.

The final question raised by Greene concerned how this Compton oak came to be the lone hybrid of its species growing at Boush Creek. Responding to a request from Baldwin, Brouwers provided further details to Palmer in a letter dated February 17, 1947. In that correspondence from Brouwers to Palmer, Brouwers explained that:

“There was another tree similar to this growing not far away from this tree – near the shores of Bousch (sic.) Creek – its leaves were larger, broader, and not quite so persistent. The nearest Live Oak to these two trees was about one-half mile away. During the war, this area was taken over by the Government; hence all trees in this location were destroyed.”

I checked historic maps that refer to an area in Norfolk once called Boush Creek. The name derives from the first colonial mayor of Norfolk City, Samuel Boush, appointed by King Charles II, in 1736. Boush was a wealthy landowner in Norfolk City. According to the map, Bosch Creek was located at northern edge of Norfolk City on Willoughby Bay. There is nothing in that area with that designation on modern maps.

The “legend” refers to Pungo as the place of origin for the young Compton Oak. That is an area southeast of Norfolk and south of Virginia Beach. However, there is no reference to Pungo, or Virginia Beach, in any the documents I reviewed at the archives as being the original location of this tree. I am not sure how that reference comes into the description of the original location of the tree. Perhaps there was a small creek in the Pungo area that also carried the name Boush Creek in 1937.

Afterword

Thanks to garden historian Wesley Greene for the initial review of the Archive’s photographic records, for providing the background information and for communicating unanswered questions needed to begin this study. Also, thanks for the invaluable assistance of Donna Cooke, Corporate Archivist and Marianne Martin, Visual Resources Collection Librarian, at the Colonial Williamsburg’s Rockefeller Library, without whose help these materials would surely not have been found.

Rick Brown is a Master Gardener Tree Steward and a Colonial Williamsburg Arboretum Volunteer