Cultivating a Tiny Forest (Part 1)

Our once shady front yard was left a bright expanse of coarse wood chips and mangled leaves after the arborists pulled out their heavy equipment and left, that hot summer afternoon almost a dozen years ago. A freak summer thunderstorm had harbored a waterspout or small tornado when it blew in from College Creek a few days before. Our first clue that something was wrong had been seeing the underside of a muddy root ball rising 8 feet or more where a venerable old double oak previously grew. Looking at the storm, through the front window, it took a few moments to register what I was seeing.

We ran out to investigate in the pouring rain, thunder still crashing nearby, and found our oak tree fallen across the yard and blocking the street. Another old oak was twisted off about 15’ up its trunk, with many smaller trees and shrubs lying under their debris. We lost so many trees that day that the entire character of our yard was transformed.

The arborists chipped up all the debris and left it piled in our yard. By the time they finished, we had at least five inches of wood chips across most of the yard and full sun blazed where we had once enjoyed leafy shade. Neighborhood friends kept encouraging me to embrace the sun and plant something new. Some arrived with grocery bags of crowns, roots and rhizomes from their own gardens to help me begin again. But I missed our beautiful trees, and the cool shade they created.

Something magical happened the following spring. Tiny seedling trees began popping up through the thick blanket of wood chips. The devastated landscape showed fresh signs of life as it was rejuvenated by nature’s own forces.

Our Local Forests

Much of the Williamsburg area lost its natural tree cover by the dawn of the 19th century. Colonists cleared land for farms, homes, and businesses. Merchants and planters harvested trees to ship their lumber back to Europe. Additional trees were cleared as Virginia joined the fight for independence from England.

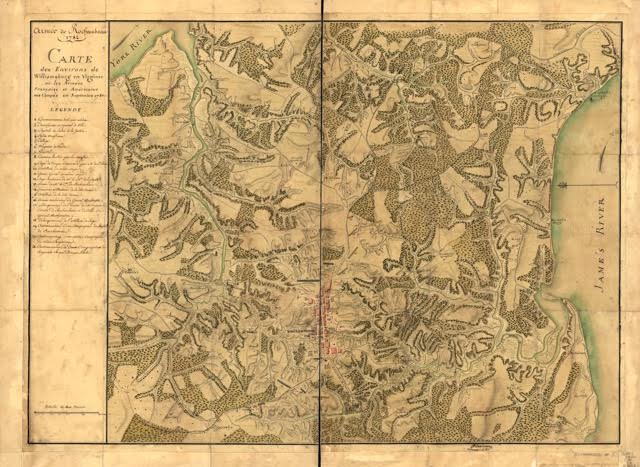

The Rochambeau map of 1785 shows much of the peninsula around Williamsburg cleared, to the extent that contemporaneous reports say that an observer could stand in the cupola atop the Wren Building and see both the James and York rivers clearly. More trees were cut in later years, particularly around the time of the Civil War in the mid-19th century.

Trees growing in our area today are relatively young trees. Many of them aren’t a part of our indigenous forest. Colonists ordered their favorite familiar trees and shrubs from Europe. Now, there have been more than 400 years of a brisk horticultural trade where trees and seeds were both imported and exported to other parts of the planet. More recently, we’ve added cultivars and improved hybrids to the mix. Like so many other areas in the world today, our indigenous, old growth forests are lost. Those forests are both the lungs of the planet, maintaining our precious atmosphere, and they are the seed bank for our forests of the future.

As we continue to lose even relatively new growth ‘forests’ to new roads and development, many of us miss their beauty. We want more trees, not fewer. As each year grows hotter than the last, we want more shade, a cooling breeze, and leafy canopies to filter harmful gases from the air we breathe. We want to hear birdsong, and we want to know that we are leaving our community better than we found it, not in a state of ecological decline.

American holly and beech trees grow along the Colonial Parkway near Jamestown. Notice there aren’t seedlings or low shrubs. This is an area that deer freely graze.

Reclaiming the Land in Postwar Japan

Japan was still recovering from the damage of WWII even as it was experiencing tremendous industrial growth in the 1960s and early 1970s. Much of the land was depleted and contaminated. The only remaining indigenous ‘old growth’ forests grew in sacred and traditionally protected places around cemeteries, shrines and temples. This was the situation facing botanist and forest ecologist Dr. Akira Miyawaki when he began mapping these forest remnants in the 1960s.

Dr. Miyawaki inventoried what trees were growing in these ancient bits of forest and began to collect and their catalog seeds. When he was hired to plant a new forest on embankments around the Nippon Steel Corporation in Oita, Japan, he designed a method to quickly re-grow a forest using indigenous trees which would have been growing on that site thousands of years ago, before it was first cleared for development. He was replacing a previous planting that had died and knew he had only three years or so to demonstrate success. Dr. Miyawaki’s planting was so successful that the corporation hired him to plant forests around its steel mills at seven additional sites in Japan.

Eastern red cedar, Juniperus virginiana, grows quickly and will live for a century or more in sun, but isn’t considered a forest species. After growing for a while in the understory it will likely die from lack of sunlight.

The Miyawaki Method for Cultivating Tiny Forests

Dr. Miyawaki developed a method to very quickly grow small forests using only native species indigenous to a particular site, from seeds he and his team collected. His methods have proven so successful that he, along with his colleagues and partners, were commissioned to plant over 1300 additional sites in Japan over the next several decades. He is credited with helping to plant over 40 million native trees worldwide. Dr. Miyawaki passed away in 2021 at the age of 93. During his long career, he also inventoried the vegetation in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, and contributed to reforestation projects in many other countries in Asia and Europe, including several in The United States.

Dr. Miyawaki’s methods to quickly regenerate small areas of native forests are simple and straightforward enough for any of us to follow. The forests bring beauty to otherwise botanically barren areas; restore ecological function to manage rainwater and cleanse the air; and grow into a seed bank of indigenous seeds that can reclaim nearby areas. They sequester large amounts of carbon dioxide. His methods are low-tech, based on ecological principles, and are very cost-effective, particularly when compared to normal landscaping practices. Dr. Miyawaki’s methods have formed the basis for various ‘rewilding’ efforts to regrow indigenous forests around the world.

Threats to Forest Regeneration

The greatest threat to natural forest regeneration, in Virginia and elsewhere, are those animals that feed on seedlings and young vegetation. The first step of ‘rewilding’ forest regeneration efforts in all regions of the United Kingdom must be to fence in and protect new forest areas from grazing sheep and cows.

At one time, hunters and predators kept our native deer population in check across much of North America. Forests could regenerate despite the deer, squirrels, voles, rabbits, and other animals which feed on acorns, nuts, and seedling trees. Our exploding deer population makes it very nearly impossible for seeds to grow to maturity where deer freely graze. Anyone planning to cultivate a tiny forest will need to plan to protect their seedling trees for the first two to three years of growth.

The Miyawaki method is designed to produce an independent forest planting in three years that can survive and thrive without additional support from the gardener. Soil preparation and close, intensive planting cause the trees to grow quickly, reaching for the available light. The interaction of the trees’ roots with fungi, and with one another, is as important to this method’s success as is the close, random planting scheme which stimulates the trees to quickly grow tall. While it may take centuries to grow a mature forest through natural succession from a grassland, this method can produce a substantial stand of trees within a few decades. By the end of the third summer the trees should be large enough to survive grazing, too.

This willow oak seedling, Quercus phellos, purchased bare root from the Arbor Day Foundation, requires protection from grazing deer.

The Miyawaki Method Principles Mimic Nature

Traditional American landscape design sites trees singly, with plenty of space left for each tree to develop. We plant specimen trees arising from a lawn or allées of matched trees along sidewalks and streets. Many reforestation efforts plant out monoculture grids of trees that grow quickly. Better projects may mix a few different species together, planted widely spaced. This isn’t how trees grow in nature. Trees naturally grow in close groupings with other plants, known as guilds.

Trees within a guild support and assist the other plants in more ways than we currently understand. Some trees fix nitrogen while others bring nutrients closer to the surface. Some trees can even ‘feed’ other plants, and help others resist disease and insect infestations, through the network of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil which links the roots systems of various plants together. Roots of plants within a guild grow together, making the group much stronger and more stable during storms than a single tree would be. To successfully regenerate our native forests, we need to plant trees as they would naturally grow after a century or more of succession.

There are a few basic steps to follow to create a successful tiny forest planting, and choices to make along the way so we tailor the planting to our site, our needs, and our resources. We can follow Dr. Miyawaki’s principles while using methods and materials available to us in contemporary Virginia.

Red maple trees, Acer rubrum, were planted spaced widely apart by park staff at Freedom Park. A tiny forest planted by the Miyawaki method would plant this space with much greater biodiversity, reflecting how trees grow wild in nature. The wooded area across the road reflects nature’s planting methods.

Steps to Grow a Tiny Forest

Identify and prepare the site

Dr. Miyawaki determined that a tiny forest could grow in as little as a few square meters of space. Many of his plantings were long, yet fairly narrow beds of trees ringing industrial sites. But some installations in urban areas were much smaller. Tiny forests can be planted around parking lots, on old commercial sites, beside roadways, in parks, and at neighborhood entrances. A 4’-5’ wide strip along the edge of a residential property is large enough to plant a tiny forest. If a few trees or shrubs grow there already, simply plant around them. A tiny forest will fill in quickly when grown in full to part sun.

Dr. Miyawakai reclaimed depleted and compacted soil by first digging to loosen the upper layer and adding compost. He wanted to re-establish the organic matter, mycorrhizal fungi, and microbes found in established forest soil before planting the trees. He also treated the area with compost tea before and after planting.

Adapting the Miyawaki Method for Contemporary Virginia

If we are planting in an area where lawn or a few trees or shrubs already grow, then a simpler method is to cover the area with paper grocery bags or other craft paper, layers of newsprint, or unglazed cardboard (that won’t repel water) to smother any grass or weeds in the area. You can buy 100′ rolls of paper at craft and hardware stores, but check to make sure it doesn’t have additives to make it waterproof.

Cover the paper or cardboard with 4”-5” of finished compost. Leaf based or mushroom compost is sold at most garden centers. Top the compost with a few more inches of arborists’ wood chips. Many arborists are happy to deliver their wood chips from work done elsewhere, for free. A reputable arborist won’t bring chips from diseased wood. Wood chips make a terrific mulch that breaks down slowly, feeds the soil, and allows for air and rain to penetrate to the soil below. Wood chips also support the growth of mycorrhizal fungi to support your new trees and connect their root systems together as part of the ‘wood-wide web.’

Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil. Fungi plays an important role in connecting trees with one another and improving the biodiversity and quality of our soils.

We also have products available to aid us in re-establishing the mycorrhizal network in the soil, which sequester carbon in addition to supporting plant growth. One easy to find product is Epsoma’s Bio-tone. Another is Worm Castings with Mycorrhizae. We can also purchase concentrated fish and seaweed, or just fish emulsion to mix with water as we water the new planting bed, and as we water in new plantings. These products build the fertility and life of the soil.

If voles are a problem in your yard, then consider installing a border around the area which extends a few inches below soil level to prevent voles from tunneling into your planting. Identify any seedling plants already growing in the area as you lay down the cardboard, and transplant desirable plants into containers to replant later. They would be buried too deeply if simply left in place under the layers of new compost and mulch.

Scarlet buckeye, Aesculus pavia, tree seedlings need to harden off in the shade before they are planted out. This species has migrated northwards into our area in the last century as the climate warms.

Acquire Plants

Dr. Miyawaki began new projects with a thorough inventory of nearby old forests to determine which species grew there as the climax community before human intervention. He determined the Potential Natural Vegetation (PNV) of a site to determine what combination of plants to use to create a multi-layered, bio-diverse planting. You will find a partial list of native plants appropriate to our area in Part 2, PNV: Potential Natural Vegetation.

Dr. Miyawaki developed a nursery to raise collected seeds, gathered from the remnants of local forests, to an appropriately sized tree to successfully transplant. His main concern was that the seedling trees had a good root system when he planted them. A damaged tree can usually regenerate if it is growing on strong roots.

Finding Plants Locally

We can acquire plants in several ways. We can collect and raise seeds produced by local trees, we can purchase native seedling trees from state forestry programs or from the Arbor Day Foundation, or we can ‘allow’ wild seedlings to emerge in our planting bed.

The easiest, most cost-effective, but least reliable method is to wait for tree seedlings to emerge. Squirrels and blue jays may hide acorns, beech nuts, hickory nuts, or other nuts that eventually germinate and grow. If these emerge in the ‘wrong’ place you can dig and translate them to your emerging tiny forest. Some seeds, like holly and Magnolia, must pass through a bird’s system, or be treated with strong acid, before they will germinate. Collecting and planting these seeds would have a very low germination rate. So, watch for these species to emerge from seeds dropped by the birds. Some seeds, like red maple or pine seeds, may blow in on the wind.

Our area is full of non-native tree species and some of these freely self-seed. Fast growing trees, from earlier stages in the succession sequence, may also emerge. These aren’t as long-lived as the climax community and may shade out, and so slow the growth of the more desirable trees you have chosen. It is important to identify any seedlings that volunteer and then remove unwanted species from the planting. Invasive species like autumn olive and Chinese tree of heaven are notorious volunteers.

Aesculus pavia, scarlet buckeye seeds are highly poisonous. They sprout easily when planted as soon as you collect them.

Once you decide on a group of species that you want to grow in your own tiny forest, you might use a combination of methods to acquire those trees you want to include. You can collect and start seeds, order some seedlings (order from state Forestry programs beginning in September for delivery the following March or April) and also watch for volunteer seedlings to emerge in your prepared bed.

Local nurseries carry some native species as established plants. These will likely be named cultivars or selections, not the species as it has developed in our local area. Each gardener will have to decide how much of a purist they want to be in this process, and how important it is to simplify the task of acquiring plants.

Liquidambar styraciflua, or American sweetgum, is a beautiful native tree with intense fall color. But many homeowners don’t like the ‘gumballs’ produced each fall that both feed wildlife and turn ankles. Allow this tree to grow only if you won’t be bothered by its hard spiky fruits.

Choose species that grow to a variety of heights so that your mature planting has different layers of vegetation. Many trees prefer some shade when young and grow faster when shaded. Some species, like loblolly pine and Eastern red cedar, grow very quickly. Consider the mature height of a tree when deciding what to plant near your home and near overhead power lines. A loblolly pine can grow to 90’.

You might choose to concentrate on trees that produce edible fruits and nuts to create a food forest, trees that host and feed wildlife, trees that bloom, or trees that have beautiful fall color. A Miyawaki forest usually included 30-50 different species, including ground cover plants. A mix of at least 25% evergreen trees will help provide a privacy screen through the winter.

Holly is difficult to grow from seeds because the seeds must be treated with acid before they will germinate. Most native trees were planted by the birds. This is an American holly that ‘volunteered’ in our yard from a seed dropped by a bird.

Estimate the total number of plants that you will need to install your tiny forest at the rate of around 3-5 plants per square meter. Not all plants will survive, but additional plants will likely volunteer. Determine a target number of plants for each species you intend to grow, keeping in mind that most will need a pollinator to produce nuts, berries, or edible fruit. Some trees, like persimmon and holly are dioeceous, meaning that you will need both a female and a male tree to produce fruit.

There are a few ways to start your own seeds. Find complete instructions in the article, ‘Growing Indigenous Trees From Seeds’ found on this website. If you want to plant your collected seeds directly into the prepared bed, first spray the seeds with an animal repellent to mask their aroma. Squirrels and other animals locate food by their sense of smell. Plant as soon as you collect the seeds, knowing that spending the winter outside will account for any required stratification to open the seed coat and allow germination to begin. You might need to protect the planted area with chicken wire, bird netting, or another barrier to protect the seeds through the winter.

You can also start the seeds in covered, plastic containers, which have drainage holes, that you leave outside through the winter. Use plastic milk jugs or large plastic boxes and a planting mix of compost, builder’s sand, and bark mulch. Once the seedlings emerge in the spring you can transplant them into larger individual containers to grow on through the summer, and then plant them into your prepared bed the following autumn. This is the closest method to how Dr. Miyawaki raised seedlings for his projects.

In addition to a mixture of trees and shrubs, you might also want to plant evergreen native ferns, or native vines and wildflowers, as a ground cover layer in your tiny forest. Spring blooming wildflowers grow well under deciduous trees because it is still bright when they are in active growth. The area will become much shadier once the trees leaf out in early summer.

Christmas ferns and lady ferns grow well in the shade. Christmas ferns remain evergreen all winter while lady ferns are deciduous perennials. Ferns grow as ground cover plants at the Williamsburg Botanical Garden and Freedom Park Arboretum.

Install and Maintain Your Tiny Forest

Late summer and early fall are a great time to plan your tiny forest and to prepare the site. There is no need to dig up the area if you prepare a raised bed with compost and mulch a few months ahead of planting. You can also add shredded leaves, pine needles, or bagged bark mulch on top of the compost and wood chips. Dr. Miyawaki mulched his plantings with straw after planting his seedlings, and then he depended on leaf litter to mulch the area in subsequent years. Arborists’ wood chips will encourage seedling trees and shrubs to volunteer from naturally dispersed seed.

Plant seeds directly in the bed in fall to overwinter, and then plant any purchased bare-root seedlings the following spring. Plant seedlings you have raised yourself from seed the following autumn. Construct some sort of fence- possibly something as simple as chicken wire on wooden supports and some bird netting- to protect the seedlings through their first few years. If your space is large enough, you might decide to lay a path through the planting during the first year while the trees remain small.

Cercis canadensis, redbud seedlings often volunteer from seeds dropped by birds. Seeds require three months of cold stratification before they will germinate.

Water the planting during dry spells for at least the first two or three years. Consider laying a soaker hose through your planting area to do this efficiently. Pull out any weeds or unwanted volunteer tree or vine seedlings during the first two or three summers as needed. Watch for Japanese stilt grass to emerge and remove it before it can spread. Many ‘weeds’ germinate from windblown seeds. By the end of the third summer, your tiny forest should be ready relatively self-sustaining and not require much additional care. While the trees should be tall enough to recover from grazing, the understory layer of smaller shrubs and perennials will still require protection from deer.

The Rewards of Cultivating a Tiny Forest

Creating a tiny forest on our land allows us to work cooperatively with nature to boost our ecosystem. The trees will attract and support a diversity of wildlife. The more biodiversity we intend, the more will appear spontaneously to use these new resources. This adventure will be full of surprises and unexpected rewards. We will enjoy the satisfaction of leaving an enduring legacy, and of leaving our home better than how we found it.

A Decade Later…

The barren expanse of wood chips in our front yard quickly evolved into a new sort of garden, better than it was before. Birds have brought us holly trees, dogwoods, redbud, Magnolias, black cherry, and lots of beautyberry shrubs. These are all from seeds that germinate best after passing through a bird’s digestive system. The squirrels contributed hickories, several species of oak, and scarlet buckeye as they hid their winter stash of food. Trees already growing in and around our yard, like tulip trees, American beech, maples, and red cedar contributed their windblown seeds. I have been astounded at how quickly these seedlings have matured in the shade of our remaining mature oak trees.

I planted many sun loving herbs and perennials over the years in and around these emerging trees and learned an important lesson. Wildlife enjoys the edges between sun and shade. Both are good. Both are necessary. A tiny forest offers sunny areas on its edges and shade within. And a tiny forest is filled with wonder, contributing to the quality and comfort of our lives.

All photos by E. L. McCoy

Continue to Part 2, PNV: Potential Natural (Native) Vegetation for a list of trees, shrubs, and ground covers for your tiny forest.

To Learn More

Darke, Rick and Douglas Tallamy. The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden. 2014.

Dirr, Michael A. Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs. 2016.

Lambe, Dan. Now Is the Time for Trees: Make an Impact by Planting the Earth’s Most Valuable Resource. 2022.

Lewis, Hannah and Paul Hawken. The Mini-Forest Revolution: Using the Miyawaki Method to Rapidly Rewild the World. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2022.

Pearce, Fred. A Trillion Trees: Restoring Our Forests by Trusting in Nature. Greystone Books. 2022.

Phillips, Michael. Mycorrhizal Planet: How Symbiotic Fungi Work with Roots to Support Plant Health and Build Soil Fertility. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2017.

Silver, Akiva and Samuel Thayer. Trees of Power, Ten Essential Arboreal Allies. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2019.

Stamets, Paul. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. Ten Speed Press. 2005

Shrubsole, Gary. The Lost Rainforests of Britain. William Collins. 2022.

Stewart, Amy. The Tree Collectors: Tales of Arboreal Obsession. Random House. 2024.

Tallamy, Douglas. Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in Our Gardens. 2007.

Tree, Isabella. Wilding: Returning Nature to Our Farm. New York Review Books. 2019.

Tree, Isabella. The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2023.

Earth Sangha Native Plant Nursery (Springfield, VA)

Missouri Department of Conservation Seedling Nurseries

Virginia Department of Forestry Seedling Nurseries