Hedges and Hedgerows for a Healthier and More Peaceful Life, Part 1

A hedge on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg serves as a background for a spring floral display. Photo courtesy of Rick Brown

The Living Fence

Gardening is the art of domesticating the wild, of creating living geometry within our landscapes. Order, symmetry, lines, and boundaries please the eye and soothe the spirit. We are inclined to organize and define our spaces by dividing them up into smaller pieces we can manage, to protect them within walls and behind gates. We contain what is ours, setting aside sacred space, our own ‘paradise,’ from the wider world. We exclude the unwanted wildness living beyond our boundaries, when we can, in ways subtle or stark.

Planting closely spaced trees and shrubs in straight or regularly curved lines creates a hedge, a living fence. This is one of the earliest forms of horticulture, aside from planting grains and vegetables. The first known hedges, planted prior to 4000 BCE, bordered fields of cultivated grain. Archeologists have found evidence of hedges planted in the earliest cultures they can study.

View of the Rockefeller Vista from the teahouse, with the Shurcliff Cedar barely visible on the right side of the path just past the boxwoods. This allée of trimmed boxwoods and hardwood trees frames the view and directs traffic to remain on the path. Photo courtesy of Rick Brown.

Earthly Paradise

Ancient temples in Egypt, Sumer, Japan, India, Greece, and elsewhere were usually surrounded by a sacred enclosure, a temenos in Greek, which contained groves, hedges, gardens, wells, and springs dedicated to the local gods and goddesses. The word ‘paradise’ comes from the ancient Persian pairi-daêza, for a garden within a walled enclosure. Visiting one of these sacred gardens allowed one to encounter the divine, or spiritual powers of the place to worship, to make sacrifices and ask for favor, and to consult oracles. Priests and priestesses tended groves of olives, tea, citrus, nut trees, herbs, and vegetables within these sacred temple gardens. In some spiritual traditions, like the early Greeks and Druids, religious ceremonies occurred in the open air within groves of trees. Many of these ancient religious observances were about increasing fertility in the land, often working with the geomagnetic energies of the Earth itself, according to researchers.

By classical times, gardens with groves and hedges surrounded the homes of royalty and the wealthy, and these patterns continue to the present in public parks and even the humblest suburban or city yard. Many Renaissance gardens were designed for viewing from the upper floors of a residence, with the garden laid out in intricate designs of hedges. Ornate parterres were surrounded by low borders of trimmed, woody herbs like rosemary or lavender, or with boxwood to enclose planting beds in various geometric designs. Seasonal displays of colorful annuals, herbs, and flowering bulbs filled the beds to create an artistic display when viewed from above.

A boxwood hedge encloses two sides of this formal parterre garden at Colonial Williamsburg. Photo by E.L. McCoy December 2015

Taller hedges, planted in geometric designs with doorways and dead ends, created mazes for the amusement of visitors. Hedges of yew, box, and Cypress grew into living walls to separate garden ‘rooms,’ and to make a back drop for floral displays. Roads on these properties were often lined with an allée of matched, carefully spaced trees which formed a continuous canopy over the drive.

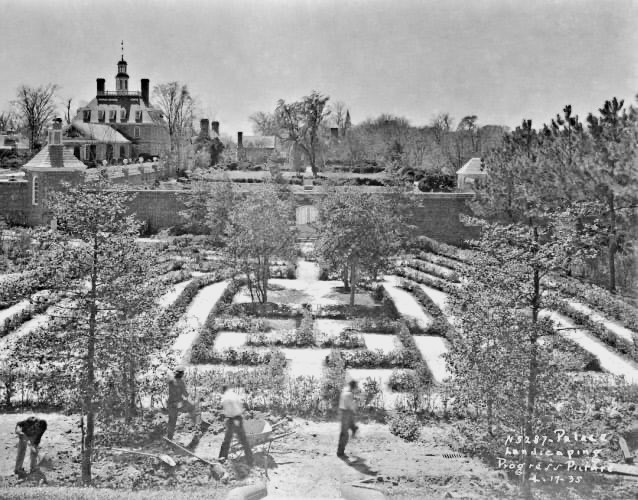

Landscape crew planting the maze in the Governor’s Palace garden, Williamsburg, Virginia, photo by Frank Nivison, April 17, 1935 Image citation: N5287. Visual Resources. Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives collection, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Traditional and Functional Hedges

We still use hedges to define the boundaries of our properties, to create privacy screens between homes, and to cover, or hide, the unattractive foundation of our buildings. A hedge is traditional and functional, and in some cases the only intentional landscaping on a property other than the lawn. We may think of the hedge as boring, and some may want to uproot their hedging to create more space for plants that support wildlife, Tallamy style. When we look more closely, and choose the right shrubs and trees, hedges and hedgerows can become the most wildlife-friendly features in our yards.

View looking out over the Governor’s Palace gardens in the process of being restored and installed with boxwood under protective wooden lattice to the right, the C&O railroad tracks to the rear, and the Virginia Electric and Power Company building in the upper left, Williamsburg, Virginia, photo by Todd and Brown Inc., circa 1934. Image citation: TB836. Visual Resources. Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives collection, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Hedges come in many sizes and forms, from low borders around planting beds to massive privacy screens of Leyland Cypress and Arborvitae found in many neighborhoods. While we may think of a hedge as only one shrub wide, perhaps 3’-5’ for a mature hedge, hedgerows of mixed trees and shrubs can make a more substantial boundary, of perhaps 15’-30’ wide. Farmers traditionally plant hedgerows as windbreaks and dividers between fields. This helps stop soil erosion during high winds and heavy rain. Hedgerow plantings can also separate types of crops and control the movement of livestock and wildlife.

Boxwood shrubs outline each bed in this parterre at the Custis Tenement Garden in Colonial Williamsburg. Photo courtesy of Rick Brown, April 2024.

Hedgerows

Hedgerows, containing various trees, may grow to 60’ tall or higher. They are planted in layers and contain a variety of species that produce flowers and fruits. A well-designed hedgerow will grow in place for centuries, supporting birds, insects, and small animals, and providing a safe corridor for wildlife to travel from place to place. Some hedgerows in England have grown in place for more than 700 years. They offer food, nectar, habitat, shelter, supporting their own ecosystem, even as they mark and divide parcels of land within a larger landscape. Hedgerows frequently separate fields and neighborhoods from nearby roads. Hedgerows may include nuts, berries and other fruits for people to harvest, as well.

Traditional farmers include tree species, like willow and hazel, that produce pliable shoots which can be bent over, interwoven, or pegged down to create a living fence or boundary within the hedgerow to contain livestock. As the bent trunks produce new, vertical shoots, these can be harvested for their wood, or they can also be bent and woven together into an impenetrable barrier. Farmers may also plant thorny species in the hedgerows and allow vines and thorny cane fruits to grow through the planting to increase biodiversity and make the area more impenetrable. Hawthorn and blackthorn are traditional, thorny species for hedgerows.

Flowering evergreen Azaleas and other Rhododendrons, planted under deciduous trees, form a popular type of hedge between properties in our area. Azaleas may be grazed by deer. Photo by E. L. McCoy April 2024.

Hedgerows in Suburbia

Many suburban homeowners adapt this idea by planting a variety of large shrubs and small trees on both sides of their fences. Whether beginning with a metal chain-link or ‘cyclone’ fence, available since the mid-19th century, or with a taller wood panel fence, that barrier can be made more attractive and more secure with a hedge or hedgerow planting. Prickly plants like hollies, Pyracantha, and shrub roses may be used along with evergreen shrubs for year-round privacy. Many plantings include some flowering shrubs like Hydrangeas, Camellias, and Japanese quince. Multi-flora roses, once recommended by the USDA for hedges, now are considered invasive.

For many homeowners, the idea of the ‘hedge’ is synonymous with ‘yard work.’ Gardeners traditionally shape and trim the hedge several times each year to maintain neatness and control the height of the hedge. Formal hedges have straight edges or are shaped to maintain a curved top. The top should be narrower than the base, however, to allow light to reach the lower branches so the hedge remains leafy all the way to its base. Foundation plantings must be regularly trimmed to keep the shrubs below window level for security and to keep them from growing over walkways and into flower beds. This is heavy work, even with power tools to assist.

Trimmed boxwood makes an attractive living fence between Duke of Gloucester Street and the John Blair house in Colonial Williamsburg. Photo by Nancy Saputo 2023, and provided courtesy of Rick Brown.

Modern cultivars offer dwarf forms of popular shrubs that require less maintenance. The struggle to maintain a tree’s size, so it looks like a small shrub, is eliminated when appropriate sized plants are selected to begin with. Homeowners may also adopt a more natural style where shrubs are allowed to grow into their own unique shapes, without regular trimming to maintain formal shapes and straight lines required in more formal settings.

J.B. Brouwers leading a tour of the Palmer House garden during the 1947 Garden & Flower Symposium, photo by Thomas Williams, 1949. Image citation: 1947-W-661. Visual Resources. Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives collection, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Maintaining Health and Well-Being

Researchers on the cutting edge of medicine and horticulture are studying how trees and shrubs improve health and well-being for those people who live near them or who regularly visit parks and forests. Not only do trees provide shade, lowering the ambient temperature during the summer, but the trees also cleanse the air of pollutants while filling the air with fresh oxygen, water vapor, and phytochemicals known as terpenes.

Terpenes are bioactive compounds, produced by plants, which allow plants to communicate with one another biochemically. They also interact with our human biology in some amazing ways to relieve stress and promote health. Scientists have proven that terpenes enhance our immune system to assist in fighting various diseases, to act as anti-inflammatories to relieve pain and promote health, to lower blood pressure, to prevent tumors, and to lift anxiety and depression.

Native mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, grows into a large but airy privacy hedge that blooms in mid-spring. Its lower trunks are visible as the plant ages. Groves of mountain laurel provide cover and safe nesting sites for wildlife. Photo by E. L. McCoy April 2023.

“Forest Medicine”

Life-expectancy increases for those who live near trees and shrubs. They have less heart disease, a lower incidence of cancer, and better mental health. Part of this can be attributed to the lower temperatures and better air quality in neighborhoods with lots of trees. Our bodies react biochemically when we are near trees by releasing certain healing hormones and molecules, including one known as DHEA, into our blood stream to protect us from heart disease. But it can also be attributed to the mental health benefits of living near trees and large shrubs, which we now know is biochemical as well as aesthetic.

In studying the interaction between terpenes and people, Japanese researchers have noticed that certain evergreen conifer trees, like cypress, cedar, pine, spruce, and fir release a high number of healthy terpenes and are the most beneficial to us. There is a whole field of ‘Forest Medicine’ in Japan which studies how forests support human health. This same research team noted that deciduous trees like oak, beech, birch, and hazel are also very effective at strengthening the human immune system. Their canopies hold the ‘good air’ at human level while absorbing ultraviolet radiation from the sun, which would break down the beneficial molecules released by plants and soil. While we don’t think of these deciduous trees as plants for hedges, evergreen shrubs and small trees are frequently used for hedges and privacy screens around homes.

Native eastern red cedar, Juniperus virginiana, is a conifer that is particularly good at cleaning pollution out of the air as it sequesters carbon in its trunk and roots. This is a fast growing tree traditionally used for allee planting at historic sites in Virginia. This cedar allee grows at the southern end of the Palace Green, between Duke of Gloucester and Francis Streets looking towards the Governor’s Palace. Photo courtesy of Rick Brown 2023

Trees Improve Health and Well-Being

An added benefit of evergreen conifers is their leaf structure, a series of needles and scales, which offer a large surface area for filtering the air, absorbing, and sequestering air pollution and greenhouse gasses year-round. Physicians and urban foresters have been working together in recent decades to learn which trees have the greatest health benefits. American researchers in urban areas now recommend conifer trees and shrubs as the most effective types of woody plants to add to neighborhoods for an immediate impact to improve residents’ health.

Those woody species we plant to improve our own personal health, and the health of our communities, also has a positive impact on our environment. Biodiversity increases exponentially as we add woody species to our yards. These trees and shrubs support many beneficial insects, which also feed birds and other small animals. The shrubs provide shelter and habitat while they also improve the soil and manage stormwater.

Eastern redbud, Cercis canadensis, is an excellent small tree to include in hedgerow plantings because it adds nitrogen to the soil. It is a member of the pea family, and its seedpods may be eaten like snowpeas. Photo by E.L. McCoy March 2024.

Trees Conserve Soil

Tree roots hold the soil against erosion as they network with fungi and bacteria in the soil. Many species, like wax myrtle and redbud trees, can ‘fix’ nitrogen that they absorb from the air into nodules stored on their roots. Some of those nitrogen-fixing woody trees, like autumn olive and mimosa, produce edible fruits, even though they appear on the list of invasive species in our area. Autumn olive fruits are particularly rich in vitamins and antioxidants. Mimosa is used in traditional Chinese medicine to relieve stress, anxiety and depression.

American colonists brought their gardening habits and favorite plants with them from Europe, and enslaved Africans brought their plants and agricultural practices with them from their homes in Africa. Both learned about the flora here in America from Native Americans. Europeans brought boxwood, both Buxus sempervirens, also known as common boxwood, and B. microphylla, or little leaf boxwood, which is a Japanese species. Boxwood is probably the most traditional plant material for medium sized, formal hedges in America and Europe. Boxwood is relatively slow growing, although common box may still grow to 10’-12’ tall if not regularly trimmed. Both boxwood species are subject to boxwood blight, various mites and insects, and damage from cold winds and saturated soils that lead to root rot, or Phytophthora.

Colonial Williamsburg replanted its yaupon holly maze in the Governor’s Palace Garden some years ago. The new planting has fencing installed with the shrubs to prevent visitors from cutting through the maze, as they did previously, thus damaging the original shrubs. Photo courtesy of Rick Brown March 2024.

Blight on the Boxwoods

Boxwood blight and root rot both are fungal infections that kill the plant, but don’t affect animals or humans. There is no known cure for boxwood blight, which first appeared in Virginia in 2011 and in the Williamsburg area just a few years later. Infected plants must be carefully removed and destroyed to minimize their contact with other boxwood nearby. Fungal spores are transmitted plant to plant by insects, animals, people, and tools used on infected plants. Pruning tools should be sanitized when moving from one plant to the next. Colonial Williamsburg has been replacing infected boxwood plantings with other shrub species.

Landscape staff unloading an Eastern Red Cedar from the back of a truck at the rear gate of the Governor’s Palace Garden, photo by Frank Nivison, March 25, 1942.

Image citation: N6850. Visual Resources. Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives collection, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Substitutes for Boxwood Hedges

Other plants that resemble and perform like box include yaupon and inkberry holly, both native and used extensively by Native Americans; Japanese holly, Ilex crenata; English holly, I. aquifolium; and privet, Ligustrum ssp. These are evergreen shrubs with relatively small, glossy leaves that stand up well to regular trimming. Many can be trimmed into topiary or planted closely to make an attractive hedge. Many of the Ligustrum species popular in the 20th century have proven so successful that they are now found on the official ‘invasive’ species lists. They bloom in spring, like hollies, and produce rich dark berries in late summer which are beloved by birds.

Japanese holly, I. crenata, is an attractive, low maintenance boxwood substitute. Photo by E. L. McCoy April 2024.

Knowledge is Power

When choosing plants for hedges and hedgerows, take time to learn as much as you can about the appropriate species before you purchase them. Most want a minimum of 6 hours of full sun each day and prefer well-drained soil. There are also many good choices for shade, including various Azaleas, Camellias, Hydrangeas and Rhododendrons. Choose shrubs and trees that will remain a manageable size for your space. Determine how closely to plant the plants so they aren’t crowded but will still interweave their branches into a continuous hedge. Spacing of 3’ is common for hedges.

Red leaf, or Japanese Photinia is a popular choice for tall, screening hedges between properties. It is very tolerant of less than ideal conditions, but is also subject to a fungal blight. Photo by E. L. McCoy April 2024.

Consider whether you want an evergreen hedge, or whether you want to include flowering plants like Forsythia or roses, which may drop their leaves in autumn. A ‘tapestry’ hedge incorporates shrubs with similar leaf texture and size in varying colors. Include gold, blue, or burgundy foliage along with various shades of green. Shrubs with variegated foliage, like Osmanthus ‘Goshiki’ and some English hollies, add sparkle to a mixed tapestry hedge.

Take the time to learn about diseases, blights, and insect pests which can affect those species you want to grow. Sometimes popular plant choices, like red-leaf Photinia and boxwood, can be suddenly wiped out or scarred by blight. Choose resistant cultivars when possible. Where deer freely graze, begin with deer resistant selections and still plan to protect those with barriers or chemical repellants for the first year or two after planting. Deer find new shrubs, full of nitrogen fertilizer from the nursery, as tasty as salted French fries. Yaupon holly, Oregon grape holly, Osmanthus and Gardenia prove more deer resistant than many other broadleaf shrubs.

Camellia sasanqua and native oakleaf Hydrangea provide abundant autumn color in mixed hedges. Photo by E. L. McCoy November 2023.

‘Cornish Hedges’ for Flood Control

In areas that flood after heavy rain, or where the water table is close to the surface, consider first building a raised bed, or a berm of topsoil where your hedge will grow, and then planting the shrub into the berm rather than directly into the ground. This is known as a ‘Devon Hedge’ or ‘Cornish Hedge,’ particularly when the berm is held in place with stone. It provides better drainage for the plants to prevent problems with root rot, or Phytophthora, and provides additional privacy to the homeowner. A raised ‘Cornish Hedge’ can also protect property and animals from high winds and minor flooding.

Landscape crew positioning one of the Twelve Apostle shrubs, all Eastern Red Cedars, in the Governor’s Palace formal garden in preparation for its planting, Williamsburg, Virginia, photo by Frank Nivison, circa 1935. Image citation: N6849. Visual Resources. Courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives collection, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Neighborly Fences

Hedging is an ancient gardening art form that remains relevant today because of the many benefits a hedge provides. Make yours useful and beautiful through careful planning and thoughtful maintenance. It can become the foundation for a healthier and more peaceful life for you and for your neighbors.

Learn more about beautiful trees and shrubs that grow well in our area:

Hedges and Hedgerows Part 2: Making Good Choices

With appreciation to Rick Brown for collaborating on this article, for providing information about boxwood blight control at the Colonial Williamsburg Arboretum, and for contributing photos from his own collection and from the Colonial Williamsburg Archives. Rick is a Master Gardener Tree Steward who volunteers with the Colonial Williamsburg Arboretum.

Hedges and topiary grow on The Governor’s Palace grounds at Colonial Williamsburg. Photo by Rick Brown March 2024.

For More Information:

Arvay, Clemens G. The Biophilia Effect: A Scientific and Spiritual Exploration of the Healing Bond Between Humans and Nature. Sounds True Publishing. 2018.

Dirr, Michael A. Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs. Timber Press. 2011.

Dirr, Michael A and Keith S. Warren. The Tree Book: Superior Selections for Landscapes, Streetscapes, and Gardens. Timber Press. 2019.

Dutton, Joan Parry. Plants of Colonial Williamsburg – How to Identify 200 of Colonial America’s Flowers, Herbs and Trees. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1979.

Greer, John Michael.

Hemenway, Toby. Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2009.

Martin, Tovah. “Boxwood is a garden workhorse. Here’s how to protect it from blight.” The Washington Post. October 17, 2023. Accessed 4.24 https://www.washingtonpost.com/home/2023/10/17/boxwood-blight-prevention/

Mellichamp, Larry and Will Stuart. Native Plants of the Southeast. Timber Press. 2014.

Mollison, Bill. Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. Ten Speed Press. 1997.

Scott, Timothy Lee. Invasive Plant Medicine: The Ecological Benefits and Healing Abilities of Invasives. Healing Arts Press. 2010.

Tallamy, Douglas and Rick Darke. Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants. Timber Press. 2009.

Tallamy, Douglas. Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. Timber Press. 2015.

Tallamy, Douglas. The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees. 2021.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. “Boxwood Blight Strikes Colonial Williamsburg.” News release. September 16, 2021.

Vogt, Benjamin. A New Garden Ethic: Cultivating Defiant Compassion for an Uncertain Future. 2017.

Virginia’s Invasive Plant List.

Virginia Tech Department of Communications and Marketing College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “Best Management Practices for Boxwood Blight in the Virginia Home Landscape.” version 2, 2016. Accessed 4.24. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/PPWS/PPWS-29/PPWS-29-pdf.pdf